81: Hot and cold on HomeKit

HomeKit launched in iOS 8 and has operated as a stealth feature for the past two years. It's powerful enough to have Siri control your lights but so invisible that you need to download a third-party app to get it working (some app, any app, not necessarily the app that goes with your HomeKit accessories). This is changing in iOS 10 with a first-party Home app and something I think is far more useful: access to HomeKit scenes and accessories in Control Center.

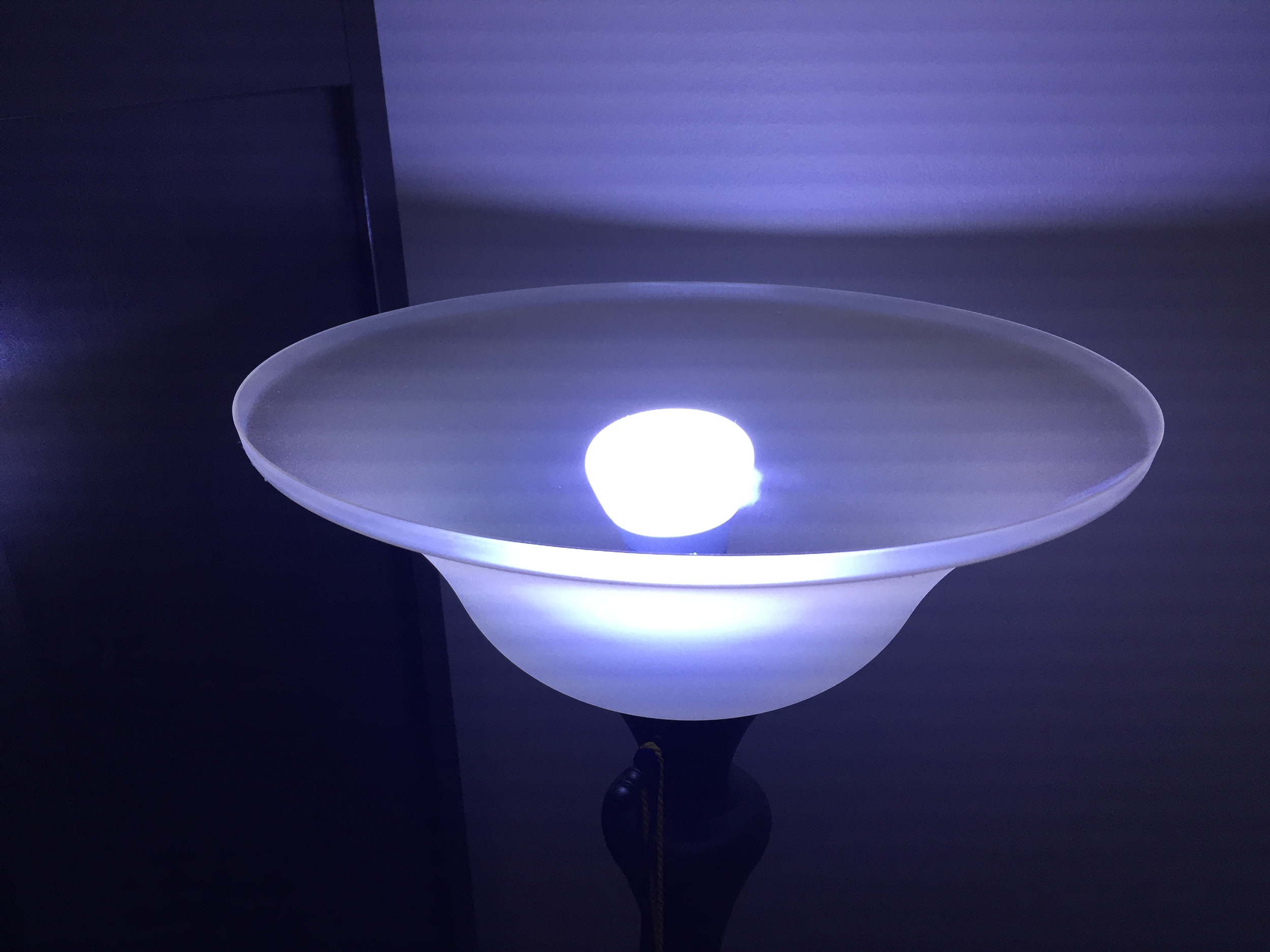

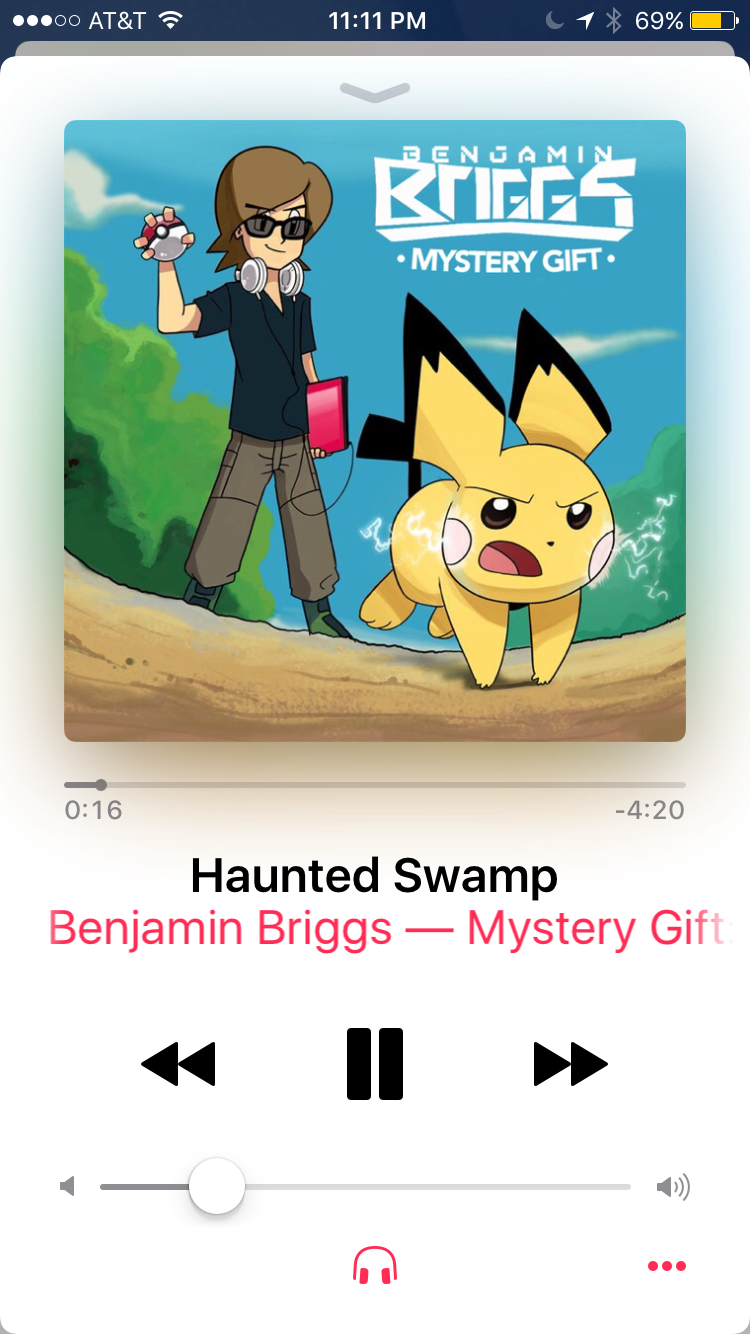

In fact, the entire third pane of Control Center is dedicated to HomeKit. (I'm not sure what people with no HomeKit devices see there. Blank space?) Devices can be switched on or off with a tap, and further controlled after a hard press or long press. For lights, that means a big sliding dimmer switch, and a button to access another screen for setting color. There you can set up six presets or dig even deeper to access color wheels. One wheel is a standard RGB rainbow, and the other controls color temperature.

If you're familiar with color temperature at all, it's probably from the desktop utility f.lux, which automatically adjusts temperature based on time of day — cooler and bluer during the day, warmer and orangier at night. Color temperature is measured in Kelvin, just like heat temperature, because there's supposed to be a direct correspondence to physical properties of ideal objects at those heats.

In reality, color matching is a mess and 5000K here may not be 5000K there. My Philips Hue bulbs, although boasting their color range on the packaging, never let me directly set a K value; I always have to choose from an onscreen color palette. Their idea of white light temperature goes from yellowy to mildly blue. Apple's, on the other hand, goes all the way to deep orange and deep blue, more Florida Gators than f.lux.

In practice, this means that what I see is not what I get in my HomeKit apps. The same bulb set to the same moderately warm tone can appear onscreen as everything from beige to green!

And I still haven't managed to set a pleasing color that feels white with Apple's wheel. Fortunately, the workaround is to set a good color in another app, then activate Control Center and set the current color to one of the presets. Having done that, HomeKit is now more useful than ever before, especially for things like quietly turning out the lights at night. But even two years in, it still requires a hodgepodge of apps to set things just right.